Stage 2 - Enquiry: Advice for Conducting an Adult Safeguarding Enquiry

10. Advice for Conducting a Adult Safeguarding Enquiry

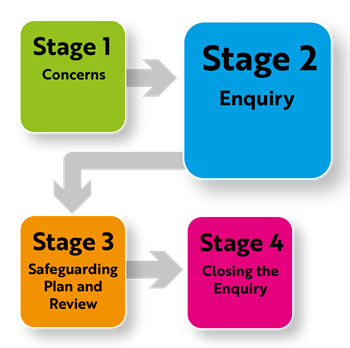

10.1 The decision-making process

The Liverpool Multi-Agency Adult Safeguarding Concern Form has been designed to provide all of the detailed and necessary information to allow colleagues in the Local Authority to effectively make a decision on if a Safeguarding Concern needs to progress to a Section 42 (or non-statutory Enquiry) under the Local Authority’s duty to do so within the Care Act 2014.

Please also refer to the Guidance for Making Decisions on Adult Safeguarding Enquiries: https://www.local.gov.uk/making-decisions-dutycarry-

out-safeguarding-adults-enquiries

All of this Safeguarding data will be collated within the Local Authority’s case management system (as the lead agency in the city) so that there is a central source of information and intelligence, which will allow this to be carefully monitored and assessed.

There is also a need to carefully consider if statutory advocacy is required.

See below more information around when to refer for an advocate.

10.2 Enquiry routes

Once a decision is made that a Safeguarding Enquiry must be conducted under the Section 42 duty, the relevant team within the Local Authority will

decide who is best placed to conduct this. When this is delegated outside of the Local Authority they will still retain the overall responsibility to coordinate

the enquiry as the lead agency, and as such they will provide the quality assurance and oversight in relation to all Safeguarding Enquiries The Liverpool Safeguarding Adults Board is currently developing it’s provider led safeguarding enquiry approach. Further guidance will be available on

this later in 2026.

10.3 Definition

An adult safeguarding enquiry (Care Act s42) is the range of actions undertaken or instigated by the Local Authority in response to an abuse or neglect concern in relation to an adult with care and support needs who is unable to protect themselves from the abuse or neglect or the risk of it.

An enquiry should be proportionate to the situation and the level of risk involved. This could be a conversation with the adult, or representative if they lack capacity, right through to a much more formal multi-agency plan or course of action.

There may need to be several different enquiries that would form part of the overall adult safeguarding enquiry. The process of undertaking enquiries should be tailored to the individual needs and circumstances of the adult. It should be proportionate to the level of risk involved and take account of the adult’s ability and capacity to make decisions for themselves. All enquiries undertaken must be lawful and take full account of the consent and wishes of the adult.

10.4 Purpose

An enquiry is the action taken or instigated by the Local Authority in response to a concern that abuse or neglect may be taking place. The purpose of the enquiry can be found in 14.77 of the Care and Support Statutory Guidance (CSSG), these are:

The AIMS of an enquiry are (14.11 CSSG):

- prevent harm and reduce the risk of abuse or neglect to adults with care and support needs.

- stop abuse or neglect wherever possible.

- learning from incidents with an open mind, without any recourse to blame.

- safeguard adults in a way that supports them in making choices and having control about how they want to live.

- promote an approach.

- raise public awareness so that communities as a whole, alongside professionals, play their part in preventing, identifying and responding to abuse and neglect,

- provide information and support in accessible ways to help people understand the different types of abuse, how to stay safe and what to do to raise a concern about the safety or well-being of an adult.

- address what has caused the abuse or neglect.

The OBJECTIVES of an enquiry are (14.94 CSSG):

- establish facts.

- ascertain the adult’s views and wishes.

- assess the needs of the adult for protection, support and redress and how they might be met.

- protect from the abuse and neglect, in accordance with the wishes of the adult.

- make decisions as to what follow-up action should be taken with regard to the person or organisation responsible for the abuse or neglect.

- enable the adult to achieve resolution and recovery.

What happens as a result of an enquiry should reflect the adult’s wishes wherever possible, as stated by them or by their representative or advocate. If they lack capacity it should be in their best interests if they are not able to make the decision, and be proportionate to the level of concern.

The process of undertaking enquiries should be tailored to the individual needs and circumstances of the adult. It should be proportionate to the level of risk involved and take account of the adult’s ability to self-protect and their capacity to make decisions for themselves. All enquiries undertaken must be lawful and take account of the consent and wishes of the adult.

The immediate priority should always be to ensure the safety and well-being of the adult. Wherever practicable the consent of the adult should be sought before taking action. What happens because of an enquiry should reflect the adults’ wishes wherever possible, as stated by them or by their representative or advocate.

If they are assessed as lacking capacity to make relevant decisions, a best interest decision will need to be taken around those relevant decisions and / or actions which must be proportionate to the level of risk identified. If there is a dispute in relation to best interests that cannot be resolved, and/or, if the person objects to the best interests decision, legal advice should be sought.

Whether or not the adult has capacity to give consent, action may need to be taken if others are or will be put at risk if nothing is done or where it is in the public interest to take action because a criminal offence has occurred.

It is essential that coercion, control and duress is considered in assessing a capacitous adult’s ability to give true consent to being involved in the enquiry. However, the adult should always be involved from the beginning of the enquiry unless there are exceptional circumstances that would increase the risk of abuse (14.80 CSSG).

If the adult is presumed to have capacity to give consent and does not want any action taken, their wishes should be respected wherever possible. However, there will be exceptions when a professional must override the adult’s wishes for example when others are at risk of abuse or neglect, a breach of regulation, where the risks are considered to be high or a criminal offence appears to have been committed. Where there is a requirement to override an adult’s wishes, the adult must be informed of this (where safe to do so) and all information documented, providing evidence of any alternative considered and the rationale for overriding the adult’s wishes.

10.5 Roles and responsibilities

The Local Authority cannot delegate its duty to conduct a formal s42 enquiry, but it can cause others to make enquiries. This means that the Local Authority may ask a provider or partner agency to conduct its own enquiries, and report these back to the Local Authority in order to inform the Local Authority decision about whether and what action is required.

Where a crime has or may have been committed the Police are responsible for conducting a criminal investigation.

While the Local Authority has overall responsibility and the duty to conduct enquiries, this does not absolve other agencies of safeguarding responsibilities.

Relevant partner agencies involved in providing services to adults who may have care and support needs have a legal duty to cooperate in formal adult safeguarding enquiries.

Of note Section 6, of the Care Act 2014 describes a general duty to co-operate between the Local Authority and other organisations providing care and support. This includes a duty on the Local Authority itself to ensure co-operation between its adult care and support, housing, public health and children’s services. Local authorities and their relevant partners must respond to requests to cooperate under their general public law duties to act reasonably.

Section 7, Care Act 2024 supplements the general duty to cooperate in section 6 with a specific duty. This duty is intended to be used by local authorities or partners where cooperation is needed in the case of an individual who has needs for care and support. The duty is not limited to specific circumstances, but could be used, for example, when a child is preparing to move from children’s to adult services; in adult safeguarding enquiries; when an adult requires an assessment for NHS continuing healthcare; or, when an adult is moving between areas and requires a new needs assessment.

This includes sharing information to enable the enquiry to be made thoroughly, participating in the enquiry planning processes, and undertaking enquiries when they have been ‘caused’ by the Local Authority to do so.

10.6 Timeliness

The indicative timescale for planning an enquiry is 2 days, this will include undertaking an initial assessment of risk, and for deciding what safety and protection actions need to be put in place while enquiries are undertaken (i.e. the interim safeguarding plan). If an enquiry planning meeting is required it is expected this will occur within 5 days of deciding an adult safeguarding enquiry needs to take place. Some cases may have more immediate risks and may need a swifter response.

10.7 Enquiry Planning

All enquiries need to be planned and coordinated.

No agency should undertake enquiries prior to a planning discussion or meeting unless it is necessary for the protection of the adult or others or unless a serious crime has taken place or is likely to.

Planning should be seen as a process, not a single event.

The planning process can be undertaken as a series of telephone conversations, or meeting/s with relevant people and agencies. In some cases the complexity or seriousness of the situation will require a Planning process to include a formal meeting/s.

Urgency of response should be proportionate to the seriousness of the concerns raised, and the level of risk.

Planning processes should be tailored to the individual circumstances of the case, but should cover the following aspects:

- gaining the views, wishes, consent, and desired outcomes of the adult (or planning how these views and wishes will be gained);

- deciding if an independent advocate is required (or planning how information will be gained to enable this decision to be made);

- gathering and sharing information with relevant parties;

- assessing risks, and formulating an interim safeguarding plan to promote safety and wellbeing while enquiries are undertaken.

The Planning process will be led and coordinated by the Team Manager from the Local Authority however they may delegate this to a senior practitioner / social worker when the level of risk and / or complexity allows.

Appropriate levels of information should be shared with, and involvement gained from, relevant partners.

Information sharing and who should be involved in enquiry planning will be dependent on the individual situation and will be decided by the Team Manager (or the person they have delegated to). As a general principle, and as long as this does not cause undue delays, all relevant agencies and individuals who have a stakeholder interest in the concerns should be involved in the process in the most appropriate way (taking into consideration issues of consent, risk, and preserving evidence).

Information sharing between organisations is essential to safeguard adults at risk of abuse or neglect. Decisions about what information is shared and with whom will be taken on a case-by-case basis. Whether information is shared with or without the adult’s consent, the information shared should be:

- necessary for the purpose for which it is being shared

- shared only with those who have a need for it

- be accurate and up to date

- be shared in a timely fashion

- be shared accurately

- be shared securely

If the adult has the mental capacity to make informed decisions about their safety and they do not want any action to be taken, this does not preclude the sharing of information with relevant professional colleagues. This is to enable professionals to assess the risk of harm and to be confident that the adult is not being unduly influenced, coerced or intimidated and is aware of all the options. This will also enable professionals to check the safety and validity of decisions made. It is good practice to inform the adult that this action is being taken unless doing so would increase the risk of harm. There are some key partner agencies and individuals that should always be notified of concerns, and be involved where appropriate, in the following circumstances.

| Circumstances |

Report to: |

| Where it is suspected that a crime has been or might be committed. |

Police |

| Where quality and safety concerns arise about a service registered under the Health and Social Care Act 2008. |

Care Quality Commission Local Authority Contract and Commissioning service. Local Integrated Care Board if there is a health funded contract. |

| Where quality and safety concerns arise about a NHS service or an Independent hospital. |

Care Quality Commission Local Authority Contract and Commissioning service. Local Integrated Care Board if there is a health funded contract. |

| Where disciplinary issues are involved |

Manager of relevant agency. |

| Where there has been a sudden or suspicious death |

The local Coroner’s office. |

| Concern occurred in a health / social care setting, and involved unsafe equipment or systems of work. |

Health and Safety Executive (HSE) |

There is a duty to involve the adult in a safeguarding Enquiry

The adult (or their representative or advocate where indicated) must be involved in Enquiry processes, including in Planning the Enquiry, wherever this is appropriate and safe.

10.8 Enquiry planning meetings

Where the enquiry is complicated and requires a number of actions that may be taken by others to support the outcome, it may be appropriate for an enquiry planning meeting. Where enquiries are simple, single agency enquiries it may not be necessary to hold a meeting. Action should never be put on hold, due to the logistics of arranging meetings. Proportionality should be the guiding principle. If the adult wishes to participate in meetings with relevant partners, one should be convened. Action, however, should not be ‘on hold’ until a meeting can be convened. If the adult is not able to attend for any reason, then an advocate could represent their views.

| Enquiry planning meetings (when required) should be completed within 5 days of receipt of the enquiry or sooner depending on the level of risk – Same day enquiry planning meetings can be held. Enquiry planning meetings should not be limited to the start of the enquiry and can be held at any point during the enquiry where the need for a meeting arises. |

Enquiry planning meetings are indicated in the following circumstances:

- complex or high risk enquiries

- domestic abuse

- forced marriage, female genital mutilation or honour based abuse

- modern slavery

- repeat safeguarding concerns

- multi-agency involvement with a person

- several agencies have concerns and the sharing of information is advisable

- several people are or could be at risk

- there are indications that a number of safeguarding enquiries are being undertaken (or could be)

- Hoarding / Self neglect

The Team manager (or the person they have delegated to) who is setting up and chairing the Enquiry planning meeting must seek to understand the adult’s views, wishes and opinions are effectively represented, and conduct the meeting in an appropriate manner, using appropriate adaptations if required, allowing for the full participation of the adult and or their representative(s).

The enquiry planning meeting should consider:

- The details of the Safeguarding Concern and how this places the adult at risk of abuse or neglect.

- How the enquiry is to be conducted and which agencies will undertake actions.

- How the adult will be fully involved in the enquiry.

- That there is clarity about the type of abuse that has occurred and that this is recorded effectively, considering types of abuse that are particularly under-recorded:

- Organisational Abuse

- Discriminatory Abuse

- Modern Slavery

- Domestic Abuse.

- That an appropriate risk assessment of the available information is conducted that informs decisions regarding how the enquiry will be undertaken, by whom, and by when.

- How an interim Safeguarding Plan will be delivered to reduce or remove the risk of harm to the adult, and or others.

- Any potential risks to children and young people (or other adults at risk) and agreement on who will arrange a Child Protection referral, where necessary.

- The link with other key processes and procedures e.g. personnel issues (including referrals to the Disclosure and Barring Service or a professional or regulatory body); Police investigations; other regulatory processes such as a NHS PSIRF.

- How everyone involved in the enquiry will deliver the actions that are agreed as a result of the enquiry in a manner consistent with Making Safeguarding Personal principles (MSP) and that the adult’s views and wishes are achieved as agreed.

- That arrangements are in place to give feedback to the person raising the Safeguarding Concern if they are not in attendance at the Safeguarding Concern Meeting where appropriate'.

Who can convene an Enquiry Planning Meeting?

The Local Authority can convene an Enquiry Planning Meeting.

Who should attend an Enquiry Planning Meeting?

There are a wide range of people who may be required to attend a Safeguarding Meeting, including, but not limited to:

- The adult and or their representative

- The Team Manager / senior practitioner or their equivalent.

- The Safeguarding Enquiry Officer usually the allocated social worker

- The person who raised the Safeguarding Concern (if they are a professional).

- Police manager.

- Other criminal justice agencies.

- NHS Trust manager and or relevant specialist.

- GP

- Care Quality Commission.

- Care Provider agency manager.

- Relevant Liverpool City Council or Integrated Care Board (ICB) Commissioner.

- Quality Assurance or Contracts Officer from Liverpool City Council or Liverpool Place - ICB.

- The person/agency alleged to have caused the harm should have been given the opportunity to submit their representations. If this an agency, then a manager

- Any other relevant agency/service representative as deemed appropriate by the person chairing the meeting.

Whoever attends an enquiry planning meeting should be of sufficient seniority to make decisions within the meeting concerning the organisation’s role and the resources they may contribute to the enquiry and agreed Safeguarding Plan.

Safeguarding Meetings can be formally recorded and minutes taken, which should be shared with those attending. When minutes are taken these should be completed within 5 working days of the Meeting.

Where it is not possible for a minute taker to be arranged then action notes should be taken this will be especially relevant to those enquiries that are less complex but do still require a Safeguarding meeting.

10.9 Consent and engagement with the adult in relation to a Safeguarding Enquiry

These are often crucial factors in determining if a Safeguarding Enquiry can progress, and how effective it is, and may lead to decisions not to proceed that leave the adult still exposed to a risk of significant harm.

These are often crucial factors in determining if a Safeguarding Enquiry can progress, and how effective it is, and may lead to decisions not to proceed that leave the adult still exposed to a risk of significant harm.

- Read The Caldicott Principles.

- Whilst consent is not required, best practice requires you to consider does the adult have the mental capacity to consent to the Safeguarding Enquiry?

- Is there a need to provide statutory advocacy

- Is there any possibility that the adult has/ is suffering from any type of coercion, control, threat, duress or pressure from another person(s) which may mean they refuse consent?

- Does mental capacity (including executive capacity) need to be assessed or reviewed? For more information read: Decision Making and Mental Capacity (NICE Guidelines), Supported decision-making toolkit for people with communication difficultiesPracticable steps for people with communication difficulties and Oldham SAB's Executive Functioning Guidance

- Give due regard to the adult’s views and wishes, including their desired outcomes, even if Best Interest Decisions have been made linked to the Mental Capacity Act. For more information read: Local Government Association - Making Safeguarding Personal Toolkit including on the six Safeguarding Principles and Alcohol Change UK Cognitive Impairment Guide and Alcohol Change UK How to use legal powers to safeguard highly vulnerable dependent drinkers guide.

- If the adult does have the mental capacity to consent to the Safeguarding Enquiry, but refuses, professionals must be careful that they consider how to keep the adult safe as the duty to undertake the enquiry remains in place. This may be particularly relevant in domestic abuse cases.

- A Safeguarding Enquiry can still proceed without the adult’s consent if ‘vital’ or ‘public’ interest considerations apply.

- If the adult meets the safeguarding duty/ criteria, and is at risk of significant harm, and it is deemed they do have the mental capacity to refuse consent and to not engage with any Safeguarding Enquiry, then consider seeking legal advice and the use of the Court of Protection, and or Inherent Jurisdiction: 39 Essex Chambers: Guidance on Use of Inherent Jurisdiction.

- See and use the Guidance on Improving our Approach to Adult and Family Engagement which includes an overview of Trauma Informed Practice.

- See and use the Multi-agency self-neglect and hoarding policy

- Professionals must consider escalating decision making where necessary in more complex cases, and respectfully challenge decision making if necessary and appropriate

- This links to the subject of Professional Curiosity as it is good practice to respectfully challenge safeguarding decisions that you believe are not appropriate.

10.10 Making Safeguarding Personal during a Safeguarding Enquiry

Making Safeguarding Personal (MSP) is an initiative which aims to develop a person centred and outcomes focus to safeguarding work in supporting people to improve or resolve their circumstances.

Strengths based approach

Wherever possible, every conversation with the adult (or their representative) should be from a strengths perspective. This means that before you talk about external solutions to help achieve an outcome or manage a risk you must support the adult to explore whether there is:

a. Anything within their own power that they can do to help themselves; or

b. Anything within the power of their family, friends or community that they can use to help themselves.

A strengths based approach is empowering for the adult and gives them more control over their situation and how best to resolve any issues in the best way for them. The end result may still be that the local authority or another organisation intervenes, but this decision will have been reached knowing that it is the most proportionate response available.

Adopting a strengths based approach involves:

a. Taking a holistic view of the adult’s needs, risks and situation in the context of their wider support network.

b. Helping the adult to understand their strengths and capabilities within the context of their situation.

c. Helping the adult to understand and explore the support available to them in the community.

d. Helping the adult to understand and explore the support available to them through other networks or services (e.g. health).

e. Exploring some of the less intrusive/intensive ways the local authority or other organisations may be able to help (such as through prevention services or signposting).

What MSP Seeks to achieve:

- A personalised approach enabling safeguarding to be done with and not to people, using practical methods defined by the adults' individual needs rather than those of the organisation.

- The outcomes an adult wants, by determining these at the beginning of working with them, and ascertaining if those outcomes were realised at the end.

- Improvement to people’s circumstances rather than on ‘investigation and conclusion’.

- Utilisation of person-centred practice rather than ‘putting people through a process’.

- Good outcomes for people by working with them in a timely way, rather than one constrained by timescales.

- Improved practice by supporting a range of methods for staff learning and development.

- Learning through sharing good practice.

- Further development of recording systems in order to understand what works well.

- Broader cultural change and commitment within organisations, to enable practitioners, families, teams and the Liverpool Safeguarding Adults Board to know what difference has been made.

|

Safeguarding Principle - Empowerment

What does this mean for the professionals: Adults are encouraged to make their own decisions and are provided with support and information.

What does this mean for the adult: "I am consulted about the outcomes I want from the safeguarding process and these directly inform what happens".

Local Government Association - Making Safeguarding Personal Toolkit

|

Practice approaches to adult safeguarding should be person-led and outcome focused.

The Care Act ethos and statutory guidance emphasise a personalised approach to adult safeguarding that is led by the individual, not by the process. It is vital that the adult feels that they are the focus and they have control over the process. This is not simply about gaining an individual’s consent, although that is important, but also about hearing their views about what they want as a outcome. This means, in essence, that they are supported and given an opportunity at all stages of the safeguarding process to say what they would like to be different and change; this might be about not having further contact with a person who poses risk to them, changing an aspect of their care plan, asking that someone who has hurt them apologises, or pursuing the matter through the criminal justice system.

The adult’s views, wishes and desired outcomes may change throughout the course of the enquiry process. There should be an ongoing dialogue and conversation with the adult to ensure their views and wishes are gained as the process continues, and enquiries re-planned should the adult change their views.

Sometimes, people may have unrealistic expectations of what can be achieved through the safeguarding procedures, and they should be supported to understand from the outset how their desired outcomes can be met.

The views, wishes and desired outcomes expressed by the adult are important in determining the appropriate and proportionate response to the concerns raised, and what enquiries may be needed. The person’s wishes and desired outcomes, however, are not the only consideration as sometimes actions are required without a person’s consent, particularly where there are overriding public interest issues, or risk to others. In these circumstances, the practitioner will need to ensure that a sensitive conversation takes place with the adult to explain how and why their wishes have to be over-ruled, listening to their feelings and the impact this action will have on them, and seeking to provide them, wherever possible, with reassurance.

The views, wishes and desired outcomes of the adult are equally important should the adult lack mental capacity to make informed decisions about their safety and protection needs, or have substantial difficulty in making their views known and participating in the enquiry process. Personalised practice approaches should still be taken in such cases, including engaging with the persons representative/s, any best interest consultees, appointing an independent advocate where appropriate, using what information is known and finding out what the adult would have considered important in decisions about their life, and by following best practice as laid out in the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice 2007.

10.11 Independent advocacy and “substantial difficulty”

Independent Care Act Advocacy (ICAA) is a statutory advocacy role that was introduced in the Care Act 2014. An adult is legally entitled to advocacy if they meet certain criteria.

A Care Act Advocate can support an adult if they have difficulties being involved in or making decisions about their care and support needs.

The aim of advocacy is to ensure the person is able to participate in decisions being made about their care, support and safety, to better enable their wellbeing.

An advocate can support a person if they have “substantial difficulty” taking part in assessments and reviews of their care needs, or participating on safeguarding enquiries.

Substantial difficulty is defined in the Care Act. Advocates are independent of the decision makers. An Advocate will support a person and be involved in several processes that are undertaken by the local authority such as:- Care Act assessments, Care and Support planning, Care reviews or Safeguarding.

Under what circumstances can an ICAA be allocated if an appropriate person has been identified?

In general, under the Care Act (2014), a person with a substantial difficulty in being involved in their assessment, plan or review will only become eligible for an ICAA when there is no other appropriate person to support them. However, the Care Act (2014) does specify 3 exceptions to this:

- Where the person is likely to be accommodated in an NHS hospital for a period of 28 days or more.

- Where the person is likely to be accommodated in a residential home or care home for a period of 8 weeks or more; or

- Where there is a disagreement or dispute between Liverpool City Council and the appropriate individual advocating on behalf someone with and care and support needs, and they both agree that the involvement of an Independent Advocate would be beneficial to the person.

If, under these circumstances, Liverpool Council believe that the person requires support to facilitate and maximise their involvement an ICAA must be made available, regardless of the involvement of an appropriate person.

Local Authorities have a duty to involve the adult in a safeguarding enquiry. Involvement requires supporting the adult to understand how they can be involved, how they can contribute and take part, and lead or direct the process.

As part of the Planning process, there is a need to consider and decide if the adult has “substantial difficulty” in participating in the adult safeguarding enquiry. Professionals should make all reasonable adjustments to enable the person to participate before deciding the person has “substantial difficulty”.

“Substantial difficulty” does not mean the person cannot make decisions for themselves, but refers to situations where the adult has “substantial difficulty” in doing one or more of the following:

- understanding relevant information: many people can be supported to understand relevant information, if it is presented appropriately and if time is taken to explain it;

- retaining that information: if a person is unable to retain information long enough to be able to weigh up options, and make decisions, then they are like to have substantial difficulty in participating;

- using or weighing that information as part of the process of being involved: a person must be able to weigh up information, in order to participate fully and express preferences for or choose between options;

- communicating their views, wishes or feelings: a person must be able to communicate their views, wishes and feelings whether by talking, writing, signing or any other means, to aid the decision process and to make priorities clear.

Where an adult has “substantial difficulty’” being involved in the adult safeguarding enquiry, the Local Authority must consider and decide whether there is an appropriate person to represent them.

This would be a person who knows the adult well, and could be, for example, a spouse, family member, friend, informal carer, neighbour, Power of Attorney. The identified person will need to be willing and able to represent the adult. An appropriate person to represent the adult cannot be a person who is involved in their care or treatment in a professional or paid capacity. The person who is thought to be the source of risk to the adult may be the most readily identifiable person to represent them, for example, if the person thought to be the source of risk is a spouse, next of kin, or person closest to the adult in their social network. In such circumstances, careful thought needs to be given to who is appropriate to represent the adult, but it is unlikely that the Local Authority would consider that it is in the adult’s best interests to be represented by a person who may pose a risk of harm to them. Where an adult has “substantial difficulty’” being involved in the adult safeguarding enquiry, and where there is no other appropriate person to represent them, the Local Authority must arrange for an independent advocate to support and represent them.

|

Is there a duty to provide an Independent Advocate

Has the adult substantial difficulty in expressing their views? Yes

Having made reasonable adjustments, do they still have difficulty? Yes

Is there an appropriate person who is willing and able to support them? No

There is a duty to provide an independent advocate.

|

If a safeguarding enquiry needs to start urgently then it can begin before an advocate is appointed but one must be appointed as soon as possible. If an independent advocate is appointed, they must be included fully in enquiry planning and all of the safeguarding processes to represent the views and wishes of the adult in any decisions that are made.

Find out more information here in relation to advocacy:

Liverpool Advocacy Hub | n-compass

Information | n-compass

10.12 Reporting concerns to the police, ensuring adults have equal access to the criminal justice system.

Everyone is entitled to be protected by the law and have access to justice. Although the local authority has the lead in making enquiries in adult safeguarding matters, where criminal activity is suspected involving the police as soon as possible is likely to be beneficial in many cases.

Behaviour which amounts to abuse and neglect also often constitutes specific criminal offences under various legislation, for example:

- Physical abuse

- Unlawful imprisonment

- Sexual abuse, assault or rape

- Emotional abuse

- Hate Crime

- Domestic abuse

- Theft and / or fraud

- Certain forms of discrimination

- Wilful neglect

For the purpose of a court trial, a witness is deemed to be competent if they can understand the questions and respond in a way that the court can understand. Police have a duty to assist witnesses who are vulnerable and intimidated.

A range of special measures are available to aid gathering and giving of evidence by vulnerable and / or intimidated witnesses.

These should be considered from the onset of a police investigation, and can include:

- an immediate referral from adult social care or other concerned agency

- discussion with the police will enable the police to establish whether a criminal act has been committed. This will give an opportunity to determine if, and at what stage, the police need to become involved further and undertake a criminal investigation;

- the police have powers to take specific protective actions, such as Domestic Violence Protection Orders (DVPO);

- a higher standard of proof is required in criminal proceedings (‘beyond reasonable doubt’) than in disciplinary or regulatory proceedings (where the test is the balance of probabilities), so early contact with the police may help to obtain evidence and witness statements.

- early involvement of the police helps to ensure that forensic evidence is not lost or contaminated;

- police officers need to have considerable skill in investigating and interviewing adults with different disabilities and communication needs, in order to prevent the adult being interviewed unnecessarily on other occasions. Research has found that sometimes evidence from victims and witnesses with learning disabilities is discounted. This may also apply to others such as people with dementia. It is crucial that reasonable adjustments are made and appropriate support given, so everyone can have equal access to justice;

- police investigations should be coordinated with health and social care enquiries but may take priority. The local authority’s duty to ensure the wellbeing and safety of the person continues throughout a criminal investigation;

- appropriate support during the criminal justice process should be available from local organisations such as Victim Support and court preparation schemes;

- some witnesses will need protection from the accused or their associates (see Section 3, Adults Witnesses who are Vulnerable or Intimidated, below);

- the police may be able to arrange support for victims.

Special Measures were introduced in the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 and include a range of interventions to support witnesses to give their best evidence and to help reduce anxiety when attending court. These include the use of screens around the witness box, the use of live (video) link or recorded evidence and the use of an intermediary to help witnesses understand the questions they are being asked and to give their answers accurately.

Key Messages for Practice

Only the police can investigate crimes, NOT any other professionals or employers

Early involvement of police can increase access to justice, this optimises the ability of the police to gather evidence and increase safety of the adult at risk

Reporting crimes to the police can protect other people, can protect life, and can prevent future crimes.

Whilst consent should be a starting point (where safe to seek). There are some circumstances where you should report alleged crimes regardless of the person’s consent.

Reporting crimes /incidents to Merseyside police

If a criminal offence has occurred or may occur, there is a need to contact the Police force where the crime has / may occur.

- If a crime is in progress or life is at risk, urgent police response is required dial emergency - 999.

- If a non-urgent response is required by the police and there is a clear allegation of a crime that needs to be recorded and / or attended by the police – 101.

- These crimes can also be reported online on the Merseyside Police website or by using the following direct link https://www.merseyside.police.uk/ro/report/ocr/af/how-to-report-a-crime/

- If professionals are unsure whether a crime has been committed, they can complete the relevant form and share this with Merseyside Police Mash team who will provide advice on next steps.

10.13 Other Key Messages to support practice when undertaking enquiries:

Professional Curiosity and Critical Evaluation

Professional Curiosity is the capacity and communication skill to explore and understand what is happening within a family (or an organisational setting) rather than making assumptions, accepting things at face value, or allowing your personal values or possible unconscious bias to influence the way that that you see and interpret risk.

This has been described as the need for practitioners to practice ‘respectful uncertainty’ in applying Critical Evaluation to any information they receive, or ‘thinking the unthinkable’.

The following factors highlight the need to improve professional curiosity:

- The views and feelings of some adults can be very difficult to ascertain.

- Practitioners do not always listen to adults who try to speak on behalf of another adult and who may have important information to contribute.

- Carers can prevent practitioners from seeing and listening to an adult.

- Practitioners can be misinformed with stories they want to believe are true.

- Effective multi-agency work needs to be coordinated.

- Challenging carers and other professionals requires expertise, confidence, time and a considerable amount of emotional energy.

The key to effective safeguarding practice is to ask the right questions, including:

- Would I live here, and if not, why not?

- Would I be happy with this standard of care for a member of my family?

- What does good look like?

- Is there anything else going on in this person’s life which might be causing harm, or the potential for adult abuse or neglect?

Barriers to professional curiosity

It is important to note that when a lack of professional curiosity is cited as a factor in any safeguarding enquiry or review that this does not automatically mean that blame should be apportioned. It is widely recognised that there are many barriers to being professionally curious, some of which are set out below:

The ‘rule of optimism’.

Risk enablement is about a strengths-based approach, but this does not mean that new or escalating risks should not be treated seriously. The ‘rule of optimism’ is a well-known dynamic in which professionals can tend to rationalise away new or escalating risks despite clear evidence to the contrary.

Accumulating risk – seeing the whole picture.

Reviews repeatedly demonstrate that professionals tend to respond to each situation or new risk discretely, rather than assessing the new information within the context of the whole person, or looking at the cumulative effect of a series of incidents and information.

Normalisation.

This refers to social processes through which ideas and actions come to be seen as 'normal' and become taken-for-granted or 'natural' in everyday life. Because they are seen as ‘normal’ they cease to be questioned and are therefore not recognised as potential risks or assessed as such.

Professional deference.

Workers who have most contact with the individual are in a good position to recognise when the risks to the person are escalating. However, there can be a tendency to defer to the opinion of a ‘higher status’ professional who has limited contact with the person but who views the risk as less significant. Be confident in your own judgement and always outline your observations and concerns to other professionals, be courageous and challenge their opinion of risk if it varies from your own. Escalate ongoing concerns through your manager and by using more formal procedures if necessary.

Confirmation bias.

This is when we look for evidence that supports or confirms our pre-held view, and ignores contrary information that refutes them. It occurs when we filter out potentially useful facts and opinions that don't coincide with our preconceived ideas.

‘Knowing but not knowing’.

This is about having a sense that something is not right but not knowing exactly what, so it is difficult to grasp the problem and take action.

Confidence in managing tension.

Disagreement, disruption and aggression from families or others, can undermine confidence and divert meetings away from topics the practitioner wants to explore and back to the family’s own agenda.

Dealing with uncertainty.

Contested accounts, vague or retracted disclosures, deception and inconclusive medical evidence are common in safeguarding practice. Practitioners are often presented with concerns which are impossible to substantiate. In such situations, ‘there is a temptation to discount concerns that cannot be proved’. A person-centred approach requires practitioners to remain mindful of the original concern and be professionally curious:

- ‘Unsubstantiated’ concerns and inconclusive medical evidence should not lead to case closure without further assessment.

- Retracted allegations still need to be investigated wherever possible.

- The use of risk assessment tools can reduce uncertainty, but they are not a substitute for professional judgement, and results need to be collated with observations and other sources of information.

- Social care practitioners are responsible for triangulating information such as, seeking independent confirmation of information, and weighing up information from a range of practitioners, particularly when there are differing accounts, and considering different theories/ research to understand the situation.

Other barriers to professional curiosity.

Poor supervision, complexity and pressure of work, changes of case worker leading to repeatedly ‘starting again’ in casework, closing cases too quickly, fixed thinking/preconceived ideas and values, and a lack of openness to new knowledge are also barriers to a professionally curious approach.

Disguised Compliance

Disguised Compliance involves carers giving the appearance of co-operating with agencies to avoid raising suspicions and allay concerns.

There is a continuum of behaviours from carers on a sliding scale, with full co-operation at one end of the scale, and planned and effective resistance at the other. Showing your best side or ‘saving face’ may be viewed as ‘normal’ behaviour and therefore we can expect a degree of Disguised Compliance in all families; but at its worst superficial cooperation may be to conceal deliberate abuse, and professionals can sometimes delay or avoid interventions due to Disguised Compliance.

The following principles will help front line practitioner’s deal with Disguised Compliance more effectively:

- Focus on the needs, voice and lived experience of the adult.

- Avoid being encouraged to focus too extensively on the needs and presentation of the carers, whether aggressive, argumentative or apparently compliant.

- Think carefully about the engagement of the carers and the impact of this behaviour on the practitioner’s view of risk.

- Focus on change in the family dynamic and the impact this will have on the life and well-being of the adult. This is a more reliable measure than the agreement of carers in the professionals plan.

- There is some evidence that an empathetic approach by professionals may result in an increased level of trust and a more open family response leading to greater disclosure by adults.

- Practitioners need to build close partnership style relationships with families whilst being constantly aware of the adult’s needs and the degree to which they are met.

- There is no magic way of spotting Disguised Compliance other than the discrepancy between a carer’s account and observations of the needs and account of the adult. The latter must always take precedent.

- Practitioners should aim to ‘triangulate’ and cross-reference the information they have received to confirm or refute the facts that have been presented.

Professional Challenge - having different perspectives

Having different professional perspectives within safeguarding practice is a sign of healthy and well-functioning inter-agency partnerships. These differences of opinion are usually resolved by discussion and negotiation between the practitioners concerned, but it is essential that they do not adversely affect outcomes for adults and are resolved in a constructive manner.

If you have a difference of opinion with another practitioner, remember:

- Professional differences and disagreements can help find better ways to improve outcomes for adults and families.

- All professionals are responsible for their own actions in relation to case work.

- Differences and disagreements should be resolved as simply and quickly as possible, in the first instance by individual practitioners and /or their line managers.

- All practitioners should respect the views of others whatever the level of experience – remember that challenging more senior or experienced practitioners can be hard.

- Expect to be challenged; working together effectively depends on an open approach and honest relationships between agencies and professionals.

- Differences are reduced by clarity about roles and responsibilities, the ability to discuss and share problems, and by effectively networking.

Cultural Competence

Culturally competent safeguarding practice is essential in achieving the right outcomes, and for improving the well-being of adults from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities.

Lack of cultural awareness among practitioners can impact on their ability to effectively work with and support adults and therefore deal with abuse and neglect appropriately. This can also result in poor practice or interventions, which in turn can reduce trust in statutory agencies and create barriers for engagement with and from minority ethnic communities.

It is important therefore that practitioners are sensitive to differing family patterns and lifestyles that vary across different racial, ethnic and cultural groups. At the same time they must be clear that abuse or neglect cannot be condoned for religious or cultural reasons.

All practitioners working with adults at risk and their carers whose faith, culture, nationality and recent history differs significantly from that of the majority culture, must be professionally curious and take personal responsibility for informing their work with sufficient knowledge (or seeking advice) on the particular culture and/or faith by which the adult and their family or carers live their daily lives.

Practitioners should be curious about situations or information arising in the course of their work, allowing the family to give their account as well as researching such things by discussion with other practitioners, or by researching the evidence base. Examples of this might be around attitudes towards, and acceptance of, services e.g. health and dietary choices.

In some instances, reluctance to access support stems from a desire to keep family life private. In many communities there is a prevalent fear that social work practitioners will negatively interfere, and there may be a poor view of support services arising from initial contact through the immigration system, and, for some communities – particularly those with insecure immigration status – an instinctive distrust of the state arising from experiences in their country of origin.

Practitioners must take personal responsibility for utilising specialist services. Knowing about and using services available locally to provide relevant cultural and faith-related input to prevention, support and rehabilitation services for adults (and their family) will help support practice.

This includes:

- Knowing which agencies are available to access locally (and nationally).

- Having contact details to hand.

- Timing requests for expert support and information appropriately to ensure that assessments, care planning and review are sound and holistic.

Often for BAME communities, accessing appropriate services is a consistent barrier to them fully participating in society, increasing their exclusion and potential for victimisation.

Social Graces

The term ‘Social Graces’ is a mnemonic to help us remember some of the key features that influence personal and social identity. This helps to prompt a professional to have discussions with an adult in a more inclusive way, which in turn may help to improve their understanding of that person's life circumstances and risks they may be facing:

G Gender and Geography

R Race and Religion

A Age, Accent, Appearance and Ability

C Class and Culture

E Ethnicity, Education and Employment

S Sexual Orientation and Spirituality

Read here for more information: Social Graces: A practical tool to address inequality www.basw.co.uk.

The Challenge of Engagement and Self-Neglect

When an adult is self-neglecting, relationship based work becomes crucial and having one worker as a single point of contact may be beneficial.

Using the label “hard to engage” is damaging and may result in other professionals believing there is little point in attempting to do so, and therefore should be avoided (“seldom heard” may be a more appropriate term).

Practitioners should work together if one is struggling to achieve meaningful engagement with the adult, as another may still be able to take the lead on behalf of an Enquiry Officer in managing and monitoring risk.

Practitioners should also consider the following in helping to improve engagement with adults:

- Creative, flexible and imaginative ways to communicate with adults, including working with faith, community leaders and non-safeguarding practitioners to achieve the best outcomes.

- Producing information in a number of ways to meet individual needs.

- Involving family members appropriately to help support adults.

- The use of advocacy to engage with adults.

- Training staff to enable and improve engagement with adults.

https://liverpoolsab.org/professionals/local-policies-and-procedures/